Violence at work

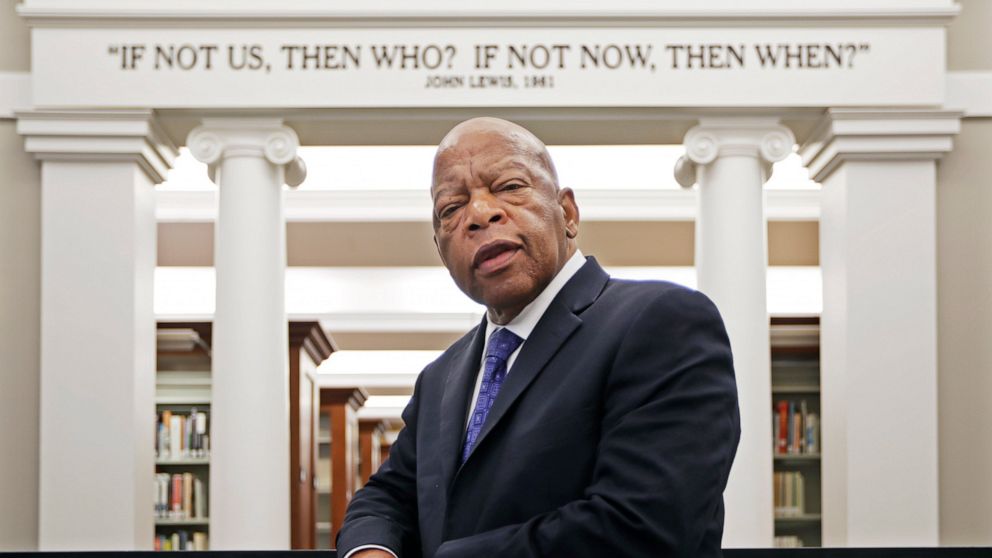

Rep. John Robert Lewis, a Georgia Democrat and civil rights icon, died Friday. He was 80 years old.

Lewis passed seven months after a routine medical visit revealed that he had stage 4 pancreatic cancer. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and the Congressional Black Caucus confirmed the news of his death.

Known as the “conscience of the U.S. Congress,” Lewis continually represented Georgia’s 5th Congressional District, which includes most of Atlanta, since taking office in 1987. His cancer diagnosis in December 2019 did not interrupt that streak.

“So I have decided to do what I know to do and do what I have always done: I am going to fight it and keep fighting for the Beloved Community. We still have many bridges to cross,” he said in a statement at the time.

“John Lewis was a titan of the civil rights movement whose goodness, faith and bravery transformed our nation – from the determination with which he met discrimination at lunch counters and on Freedom Rides, to the courage he showed as a young man facing down violence and death on Edmund Pettus Bridge, to the moral leadership he brought to the Congress for more than 30 years,” Pelosi said in a statement.

Lewis, who was born on Feb. 21, 1940 to sharecroppers in Troy, Alabama, attended segregated public schools and counted the Montgomery Bus Boycott and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s radio broadcasts as inspiration for his work as an activist.

At 18, he wrote a letter to King, who responded by purchasing a round-trip bus ticket to Montgomery for Lewis so they could meet.

“Dr. King, I am John Robert Lewis,” he recalled saying to King. “And that was the beginning.”

Lewis wasted no time organizing, quickly finding himself on the front lines of the civil rights movement.

As a student at Fisk University, he led numerous demonstrations in Nashville against racial segregation, including sit-ins at segregated lunch counters as part of the Nashville Sit-ins.

Starting in 1961, he took part in a series of demonstrations that became known as the Freedom Rides, in which he and other activists — Black and white — rode together in buses through the South to challenge the region’s lack of enforcing a Supreme Court ruling that deemed segregated public bus rides unconstitutional. Upon stopping, the activists on these rides often were arrested or beaten, Lewis included.

In his second-to-last tweet, just 10 days ago, Lewis tweeted about the 59th anniversary of his release from jail after being arrested in Jackson, Mississippi, for using a white restroom during a Freedom Ride.

During a stop in Rock Hill, South Carolina, Lewis was attacked by two men who hit him in the face and kicked him in the ribs, according to Smithsonian Magazine. In an interview decades later, he said he was undeterred.

“We knew our lives could be threatened, but we had made up our minds not to turn back,” he said.

He was the youngest person to speak at the 1963 March on Washington, an event he helped organize as the chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. The rally, at which King famously delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech, drew more than 200,000 attendees.

And in the winter of 1965, in what would become known as “Bloody Sunday,” Lewis, alongside fellow civil rights leader Hosea Williams, was in the process of leading hundreds of demonstrators in a march for voting rights from Selma to Montgomery when they were greeted by a “sea of blue” of Alabama state troopers, Lewis said. The troopers beat and tear-gassed the demonstrators after ordering them to disperse.

One of those troopers fractured Lewis’s skull, scarring his head for the rest of his life.

“I thought I saw death,” Lewis later said.

Since then, Lewis has retraced the steps from those day’s events nearly every year in what has become known as the Alabama Civil Rights Pilgrimage.

Lewis was elected to the Atlanta City Council in 1981 and then to Congress, representing Georgia’s 5th District in 1986. He has served on the Ways & Means Committee and is head of the Oversight Subcommittee.

“The world has lost a legend; the civil rights movement has lost an icon, the City of Atlanta has lost one of its most fearless leaders, and the Congressional Black Caucus has lost our longest serving member,” the caucus said in a statement. “The Congressional Black Caucus is known as the Conscience of the Congress. John Lewis was known as the conscience of our caucus. A fighter for justice until the end, Mr. Lewis recently visited Black Lives Matter Plaza in Washington DC. His mere presence encouraged a new generation of activist to ‘speak up and speak out’ and get into ‘good trouble’ to continue bending the arc toward justice and freedom.”

A published author, Lewis co-authored a graphic novel trilogy “MARCH” about the civil rights movement, a project that garnered the National Book Award among others.

Lewis was never shy in his criticism of President Donald Trump, skipping his inauguration and first State of the Union address and calling him a “racist” in a January 2018 interview on “This Week with George Stephanopoulos.”

“George, I don’t think there’s any way that you can square what the president said with the words of Martin Luther King Jr.,” the Georgia congressman said, in reaction to Trump’s alleged reference to not wanting immigrants from “s–hole” countries. “It’s just impossible … It’s unbelievable. It makes me sad. It makes me cry.”

President Barack Obama awarded Lewis the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2011 for his lifetime of advocacy and activism.

During that February ceremony, Obama said of Lewis: “And generations from now, when parents teach their children what is meant by courage, the story of John Lewis will come to mind — an American who knew that change could not wait for some other person or some other time; whose life is a lesson in the fierce urgency of now.”

Last month, at a town hall with Obama discussing the racial protests across the country following the death of George Floyd, he reflected on his emotions while protesting during the civil rights movement.

“I have been beaten on the bridge, I thought I was so dead. I thought I was going to die,” Lewis said.

“I believe it was the grace of God, and praying witnesses that helped save me, so today I feel more than lucky, more than blessed to see the changes that are occurring to live to see a young man, a young friend like Barack Obama, become president of the United States of America was worth the pain,” he added.

Lewis also offered praise for young people who had come together from all walks of life to join in protests.

“They’re going to help redeem the soul of America, and save our country, and maybe even save the planet,” he said.