Sexual harassment

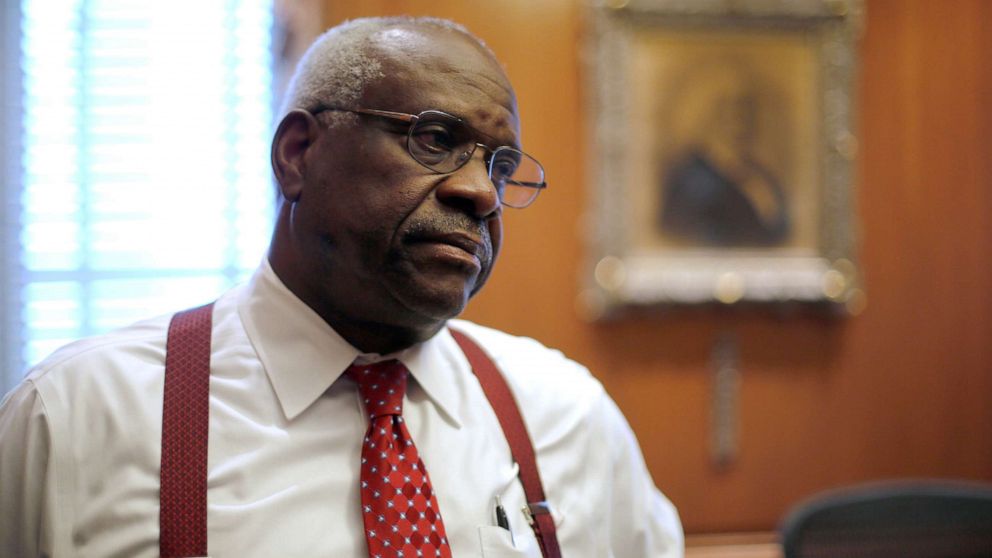

Sexual harassment New documentary revisits Clarence Thomas confirmation battle.

November 28, 2019, 10:05 AM

8 min read

Justice Clarence Thomas is joining public criticism of Joe Biden whose handling of Thomas’ 1991 Supreme Court confirmation hearings when he was a senator has been a flash point in the former vice president’s 2020 presidential campaign.

In a forthcoming documentary, “Created Equal: Clarence Thomas in His Own Words,” Thomas lashes out at Democrats and Biden, who chaired the Senate Judiciary Committee and oversaw his confirmation process.

“I felt as though in my life I had been looking at the wrong people as the people who would be problematic toward me. We were told that, ‘Oh, it’s gonna be the bigot in the pickup truck; it’s gonna be the Klansmen; it’s gonna be the rural sheriff,’” Thomas says in the film.

“But it turned out that through all of that, ultimately the biggest impediment was the modern day liberal,” he said of the experience. “They were the ones who would discount all those things because they have one issue or because they have the power to caricature you.”

ABC News was granted an early look at the documentary, which was produced by conservative filmmaker Michael Pack and Manifold Productions. It is set for theatrical release in early 2020 and is due to air on PBS next spring.

Thomas sat for more than 22 hours of interviews over a six-month period in 2018, according to the film’s publicist. Manifold has advertised the movie as a chance to “tell the Clarence Thomas story truly and fully, without cover-ups or distortions.”

The movie also casts a spotlight on Biden, who has faced renewed criticism from his fellow Democrats for his treatment of Anita Hill, an African-American law professor who had accused Thomas of sexual harassment and testified publicly before the committee during the 1991 hearings. Biden called Hill to apologize earlier this year for his handling of the case.

Thomas has categorically denied Hill’s allegations.

“Do I have like stupid written on the back of my shirt? I mean come on. We know what this is all about,” Thomas says in the film. “People should just tell the truth: ‘This is the wrong black guy; he has to be destroyed.’ Just say it. Then now we’re at least honest with each other.”

“The idea was to get rid of me,” he says. “And then after I was there, it was to undermine me.”

While Thomas does not mention Biden by name, he is asked by filmmakers to respond directly to Biden’s line of questioning during the hearings on his views of natural law.

“I have no idea what he was talking about,” Thomas says of Biden.

“I understood what he was trying to do. I didn’t really appreciate it,” he added. “Natural law was nothing more than a way of tricking me into talking about abortion.”

In response to Thomas’ comments in the documentary, Bill Russo, Biden’s deputy communications director, said in a statement to ABC News, “Then-Senator Biden voted against Clarence Thomas in the Senate Judiciary Committee, he argued against him on the Senate floor, and he voted against his confirmation to a lifetime seat on the Supreme Court. It is no surprise that Justice Thomas does not have a positive view of him.”

The Senate confirmed Thomas by a vote of 52 to 48 on Oct. 15, 1991.

“Most of my opponents on the judiciary committee cared about only one thing,” Thomas says in the film. “How would I rule on abortion rights. You really didn’t matter and your life didn’t matter. What mattered is what they wanted and what they wanted was this particular issue.”

Thomas has long been an outspoken opponent of abortion rights and urged the court to reconsider established precedent.

“Having created the constitutional right to an abortion, this Court is dutybound to address its scope,” Thomas wrote earlier this year in a concurring opinion on an Indiana abortion law.

The film is a rare opportunity to hear directly from Thomas, who is famously quiet during oral arguments and shies away from public appearances. When he asked a question in May 2019, it was the first time Thomas had spoken in the courtroom in three years.

“We are judges not advocates,” he says of his silence. “It’s not my job to argue with lawyers. The referee in the game shouldn’t be a participant in the game.”

Thomas speaks at length about his journey from childhood in impoverished rural Georgia, to a stint in a Roman Catholic seminary, and on to the elite classrooms of Holy Cross and Yale. He describes his grandfather, a fuel oil deliveryman in Savannah, as one of the biggest influences on his life, teaching him determination and self-reliance.

Thomas says those values are what sustain him in the face of persistent criticism as a black conservative.

“There’s different sets of rules for different people,” he says. “If you criticize a black person who’s more liberal, you’re a racist. Whereas you can do whatever to me, or to now (HUD Secretary) Ben Carson, and that’s fine, because you’re not really black because you’re not doing what we expect black people to do.”