Violence at work

NEW YORK —

The best news about the fall season in books is that there will be a fall season in books.

The coronavirus has shut down cineplexes, performance centers, museums and comedy clubs, but books can still be enjoyed at the scale and in the settings the creators intended. While most physical stores are offering just partial service and traditional author tours are on hold, publishing itself has so far avoided the catastrophic drops and disruptions that have left other industries wondering if they have a viable future.

“It’s been a relief, not just in a business sense but as a person, to know we’re still turning to the familiar act of reading,” says Reagan Arthur, executive vice president and publisher of Alfred A. Knopf.

“We’ve been lucky,” says Jonathan Burnham, president and publisher of the Harper division at HarperCollins Publishing. “All in all, we’ve managed to keep our business going fairly well.”

If anything, there could be too much of a fall season, the traditional showcase for literary works. Books in an election year always struggle for attention, but this year the election has never been more consuming and the publishing schedule never more crowded.

Many releases were postponed from the spring and summer as the virus spread; Barnes & Noble CEO James Daunt says the number of new books expected is up around 30 percent from the same time in 2019. Meanwhile, chronic shortages in printing capacity have led publishers to postpone some releases to 2021, among them Sasha Issenberg’s 900-page book on same-sex marriage, “The Engagement.”

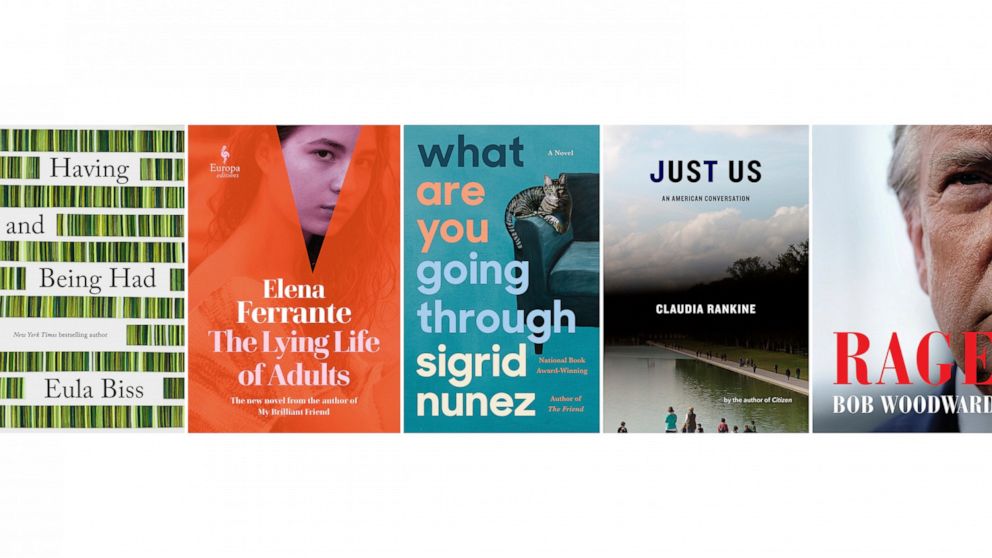

This fall is among the richest in memory for fiction, with Elena Ferrante, Marilynne Robinson, Phil Klay and Ngugi wa Thiong’o among many writers with books expected. Don DeLillo’s “The Silence” looks ahead to a shutdown and “mass insomnia” in 2022 brought on by a digital crash.

Sigrid Nunez’s first book since “The Friend,” winner of the National Book Award, looks back to a precarious, pre-pandemic world. Nunez began “What You Are Going Through” in 2017 and completed it last year, well before the virus spread. Like “The Friend,” it is a story of death and companionship, loneliness and obligation, what she calls in her book “Messy life. Unfair life. Life that must be dealt with.” Much of the book centers on the narrator’s conversations with a dying friend who has asked as a final wish that they vacation together in New England.

“The book is very clearly set before the pandemic, so I don’t think it’s in danger of seeming outdated. That’s not an issue,” Nunez says. “But in another way, strangely enough, it is (an issue). The characters do end up in a quarantine-like situation. They withdraw from the world into their own two-person pod. So it’s not the biggest stretch to think about the pandemic.”

Fiction is also expected from Hari Kunzru, Nicole Krauss, Jess Walter and Martin Amis, whose novel “Inside Story” reflects on the late Christopher Hitchens and other literary friends. Emma Cline follows her acclaimed debut novel “The Girls” with the story collection “Daddy,” and Yaa Gyasi’s novel “Transcendent Kingdom” follows her prize-winning debut, “Homegoing.”

Tana French, Jo Nesbo and Anthony Horowitz are among the crime novelists with new books, and Sophie Hannah’s “The Killings at Kingfisher Hill” brings back the Agatha Christie detective Hercule Poirot. The title of Mexican author Julian Herbert’s story collection is itself a work of suspense: ”Bring Me the Head of Quentin Tarantino” tells of “a drug lord who looks just like Quentin Tarantino, who kidnaps a mopey film critic to discuss Tarantino’s films while he sends his goons to find and kill the doppelgänger that has colonized his consciousness,” according to Graywolf Press.

Some books not only align with election headlines but may make them. Bob Woodward’s “Rage” is his latest probe into the Trump White House and a followup to “Fear,” his million-seller from 2018. Former Trump lawyer Michael Cohen lashes out at his former boss in “Disloyal,” while former National Security Advisor H.R. McMaster reflects on his 34 years of military service and 13 months in the Trump administration, in “Battlegrounds: The Fight to Defend the Free World.”

Rick Gates, a Trump campaign official who pleaded guilty to two counts of conspiracy during the Mueller investigation into alleged ties between Trump and the Russians, has written the memoir “Wicked Game.” Peter Strzok’s “Compromised: Counterintelligence and the Threat of Donald J. Trump” is a memoir by the former FBI counterintelligence agent who played a key role in the Russia investigation.

Other works touch less on Trump or the election and more on the culture around them, such as Talia Lavin’s “Culture Warlords: My Journey Into the Dark Web of White Supremacy”; Michael J, Sandel’s “The Tyranny of Merit: What’s Become of the Common Good?”; or Rick Perlstein’s “Reaganland,” the fourth and final work in his chronicle of the rise of the modern conservative movement.

Eula Biss’ “Having and Being Had” is a personal and historical look at class and consumerism that draws on everything from Marxist theory to the kind of furniture she owns. Although the book is not directly political, Buss says Trump’s rise was “rumbling” in the background as she wrote it.

“I very much think of this as a Trump-era book,” says Biss, whose “Notes From No Man’s Land: American Essays” won the 2010 National Book Critics Circle award for criticism. “I’m writing in this time that is riddled with increasing inequality and economic hardship and seems to be going further in that direction.”

Biographies and celebrity memoirs will range from Jonathan Alter’s book on former President Jimmy Carter to Jerry Seinfeld’s reflections on comedy in “Is This Anything?”. Soccer star Megan Rapinoe tells of her World Cup glory and her LGBTQ activism in “One Life,” while Alanis Morissette collaborated with Diablo Cody and Rachel Syme on a look at the making of the Broadway hit “Jagged Little Pill,” based on Morissette’s classic album. Memoirs also are expected from Lenny Kravitz and Peter Frampton.

“The Handmaid’s Tale” author Margaret Atwood was first known as a poet, and has a new collection, “Dearly.” Others with poetry books expected include Nikki Giovanni, Khaled Mattawa, Tyree Daye, Pulitzer Prize-winners Jorie Graham and Vijay Sephardi, and former U.S. poet laureate Billy Collins. Roxane Gay has edited an anthology of poems and essays by the late Audre Lorde, and Kevin Young edited the Library of America’s “African American Poetry: 250 Years of Struggle & Song.”

“We wanted to highlight the themes of community and struggle and the urge for freedom, and how they speak to the present moment,” Young says of the book, which includes work ranging from 18th century poet Phillis Wheatley to such 21st century prize winners as Terrance Hayes and Tracy K. Smith.

George Floyd’s killing and the Black Lives Matter protests that followed led to a summer of reading about race and racial injustice, notably Robin DiAngelo’s “White Fragility” and Ibram X. Kendi’s “How To Be an Antiracist.” The conversation continues with such new releases as Isabel Wilkerson’s “Caste,” an Oprah Winfrey book club pick that likens race in this country to the caste system in India, and Elliott Currie’s “A Peculiar Indifference: The Neglected Toll of Violence on Black America.”

Claudia Rankine’s “Just Us,” like her prize-winning “Citizen,” is a hybrid of poetry, history, personal reflection and illustrations. She writes about awkward encounters with white friends, and then allows her friends to respond.

“I really wanted to start with intimacy, ‘Just Us,’ while also pointing to big implications about what goes on between us,” she says. “People often say that individuals don’t matter when we talk about institutions, but we are the institutions. Congress is made up of individuals. The Supreme Court is made up of individuals.”